Letters to His Wife: The Patriotism of Martyr Tran Quang Long

As a prominent author in the patriotic and progressive literary movement of South Vietnam during the resistance against the United States, Tran Quang Long was renowned for his fervent revolutionary verses, which carried a powerful appeal to students, intellectuals, and the youth. Yet beyond his fiery devotion to the cause, he also nurtured a profound and beautiful love for his wife – Mrs. Ton Nu Quynh Nhu (also known as Ngoc), the daughter of the late Professor Ton That Duong Ky.

Ảnh đám cưới của Trần Quang Long và Tôn Nữ Quỳnh Như ngày 5/8/1967

“Because life itself has become you,

To have you is to have all of life.”

(A poem by Tran Quang Long dedicated to Quynh Nhu)

Their love was passionate, profound, and deeply responsible – for it was placed within an even greater love: love for the nation. The letters they exchanged during their years apart bore witness to this truth.

Among the memorabilia donated by the family of Martyr Tran Quang Long to the Vietnam Fatherland Front Museum are more than fifty letters he wrote to his wife, and over twenty of hers written to him.

Turning the fragile pages, now yellowed with time, one finds letters hastily penned in half a page, and others stretching across eight to ten pages. Yet in all of them remains intact the tender affection of husband and wife, inseparably intertwined with love of country, with the yearning for peace and independence, and with the noble ideal that “when the nation calls, they know how to live apart.” This young couple, united in ideals and devotion, gave their youth to the country and lived each moment of their lives to the fullest.

And yet, Tran Quang Long – the sensitive, profound, and humble man – was not without moments of anguish over his responsibilities to the nation.

In a letter to his wife dated November 13, 1967, he confessed:

“At times, I even feel a sense of guilt, of self-contempt, when I think that I have not shared enough in the hardships and sacrifices of those around me. We work little, live with some ease, while so many others – including the one we love and respect the most, Uncle (Professor Ton That Duong Ky) – are sacrificing all that is most precious. Are we being too selfish?”

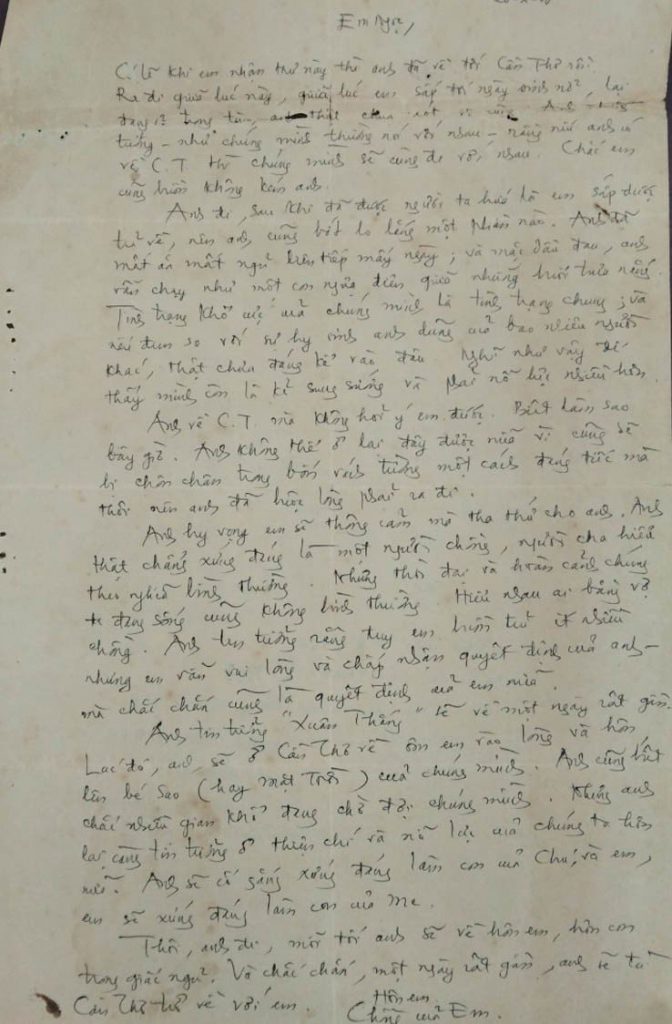

Thư ông Trần Quang Long viết cho bà Tôn Nữ Quỳnh Như (Ngọc) ngày 26-2-1968.

‘So be it’ does not mean surrendering to circumstances, but rather thinking of my friends, my comrades, our loved ones who are sacrificing so much – how could I only worry excessively about myself?”

(Letter to his wife, May 5, 1967)

The fervent heart of a citizen, a teacher, and a poet, standing before the destiny of his nation, constantly urged him to do more meaningful work for his country, drawing strength from the collective joy of the people.

In a letter to his wife dated March 27, 1967, he shared with delight how he taught his students patriotism through poems in their textbooks:

“When I see eyes suddenly shining with agreement as they listen to my allusions, I feel inspired and excited. In those moments, I do not feel as though I am teaching merely to earn a living, but as if I were giving a speech in Hue or Quy Nhon.”

He also told her how a student, moved by his poetry collection, sent him a poem titled “Cam tac” (Impressions) in admiration. That encouragement strengthened his resolve to dedicate himself more fully to the national cause. In response, he wrote verses that expressed solidarity and a call to action:

*I am touched with joy

When the hearts of friends speak out together.

Oh, you whose blood still runs warm,

Whose thirst for freedom still burns

This life belongs to us.

Let us rise and build our tomorrow.

Stand up with history,

This land is ours.

With a burning heart, I pray

That tomorrow bursts into song,

That we may grow in that faith,

That our homeland will blossom with flowers.*

For Tran Quang Long, love, joy, and marital happiness were always intertwined with the revolutionary struggle of his people. In his letter of May 5, 1967, he wrote:

“These days, the situation looks bright. Alongside the happiness our love brings, there is also the shared joy of a nation awaiting the dawn, with a gentle crimson sun rising. How could I not rejoice?”

What is striking is how he constantly measured himself against the great cause of the nation, urging himself to act with greater determination. On January 6, 1968, he confessed:

“These past days, the newspapers carry so much news that fills me with excitement. Seeing the sweeping changes around me, and then looking at my own steady, quiet days, I feel ashamed and regretful. I must strive harder. I must not waste time.”

In every circumstance, Tran Quang Long carried with him faith and optimism for life and for the future of his nation. More than that, he passed this strength on to those around him – especially to his beloved wife:

“Let us endure this short separation, do not be sad. Believe in the beautiful days to come, when our marriage will be joyful once again in the reunion with your parents, and with our people.”

(Letter to his wife, November 13, 1967)

In a remarkable letter dated February 26, 1968, Tran Quang Long even foresaw the day of national victory, as he dreamed of the names for their children:

“If it is a son, he will be Tran Xuan Thang; if a daughter, Ngoc Chan. When peace comes, I will bring home a thick volume of poems just for you. I believe that ‘Xuan Thang’ (Spring of Victory) will arrive very soon.”

Ông Trần Quang Long nằm điều trị bệnh viện do bị bắn gãy chân khi tổ chức biểu tình.

As a deeply sensitive man, devoted to his family, Tran Quang Long nevertheless showed resilience and courage in the most decisive moments – rising above private affections to make difficult choices for greater causes. His letter to his wife, Quynh Nhu, dated February 26, 1968, captures this poignantly:

“Perhaps by the time you receive this letter, I will have already arrived in Can Tho. To leave at such a time, when you are close to giving birth and still imprisoned, brings me unbearable sorrow. Yet our suffering is but part of the common struggle, and compared to the heroic sacrifices of so many others, ours is of little account. Thinking this way, I see that we are still among the fortunate – and we must strive even harder.

I left for Can Tho without asking your permission. What else could I do? I could not stay here, only to be locked within four walls in vain. I had no choice but to depart. I hope you will understand and forgive me. I trust that although you may feel sadness, you will accept my decision as your own – for you once agreed with me that we must be ready to endure for higher ideals, mustn’t you?”*

Beyond such moments of solemn resolve, his letters also reveal the tender, everyday emotions of a husband and father: the longing of separation, flashes of frustration, unending compassion for his beloved wife. On March 7, 1967, he confided:

“To marry a poor man, living far apart, so uncertain… I feel such pity, such love, and such admiration for you.”

Equally moving are his constant worries and gentle instructions for her health during pregnancy. On November 19, 1967, he wrote with warmth and earnest care:

“From now on, you must absolutely stop riding a motorbike. What does it matter if we spend a little more, my dear? Please, listen to me. These days I feel ‘rich.’ With 300 dong in extra allowance and 3,500 from teaching at the Army Cultural School, that’s over 6,000. So don’t worry about expenses. Live comfortably, don’t scrimp so much that it harms your health.”

Through these words, we glimpse both the poet and the ordinary man: a revolutionary willing to sacrifice everything for his nation, yet also a tender husband whose heart overflowed with love, concern, and responsibility for his family.

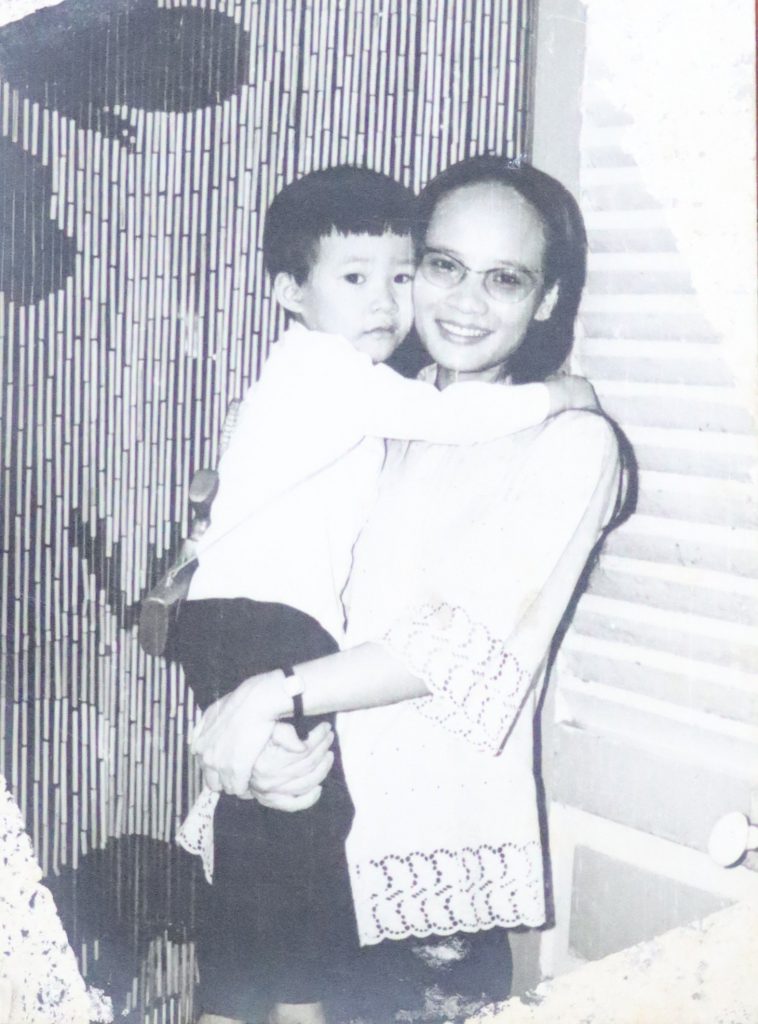

Bà Tôn Nữ Quỳnh Như và con trai Trần Xuân Thắng sau năm 1975.

Đặc biệt, ông dành thật nhiều tình cảm cho đứa con đầu lòng chưa chào đời cũng như sự thấu cảm cho những gian khổ khi vợ vừa đi học vừa mang thai mà lại không có chồng bên cạnh. Và cũng như bao người bố khác, Trần Quang Long đã khao khát ngày được nhìn thấy con chào đời, kết quả của một tình yêu đẹp, của biết bao sự đợi chờ. Bởi thế, mỗi lá thứ đều đong đầy thương nhớ, mong ngóng: “Bé Sao dạo này có đạp em lắm không? Em nhớ để tay lên bụng bảo với con rằng anh hôn bé nghe. Bảo nó đạp nhẹ nhẹ không anh la đó. Anh tưởng tượng khi được nhìn mặt con, chắc anh sung sướng đến lịm người. Chúng mình sẽ đặt con nằm giữa 2 đứa mình mà ngắm cho thỏa thích, cho bõ những ngày khổ sở của em. Em ơi, anh thương em quá khi nghĩ đến những hy sinh cực khổ của người mẹ” (Thư gửi vợ ngày 8/12/1967).

“Anh mong chóng thanh bình để anh về nhìn mặt con chúng mình. Anh buồn vì không chia sẻ khổ sở, vui sướng với em được. Em hãy chăm sóc con thật kỹ và nhớ mỗi tối, trước khi đi ngủ, hôn bé giùm cho anh một bên má, bên kia của em nhé” (Thư gửi vợ ngày 26/2/1968).

7 năm sau, Mùa Xuân toàn thắng năm 1975 đã về với dân tộc Việt Nam nhưng Trần Quang Long đã không trở về để được tận hưởng hạnh phúc của một người làm cha, được tặng người vợ mà ông hết mực yêu thương tập thơ như ông đã mong ngóng. Ngày 10/5/1968, bà Quỳnh Như sinh con trai Trần Xuân Thắng (bé Sao) khi bà đang bị địch bắt giam trong tù vì hoạt động cách mạng. 5 tháng sau, Trần Quang Long anh dũng hy sinh khi chưa kịp nhìn thấy mặt con, chưa gặp lại vợ. Và mãi hơn một năm sau, bà Quỳnh Như mới biết chồng đã hy sinh.

Anh Trần Xuân Thắng, con trai Liệt sĩ Trần Quang Long trao tặng kỷ vật cho Bảo tàng Mặt trận Tổ quốc Việt Nam.

So much grief and sorrow remains when comrade Tran Quang Long fell heroically at the age of only twenty-seven. Yet in those brief years, he lived fully – with life, with his country, and with love. His revolutionary fervor lit a torch that spread powerfully through the patriotic movements of students, intellectuals, and teachers in South Vietnam during the struggle against American intervention.

In recognition of his influence, a student association in the Federal Republic of Germany bore his name: the Tran Quang Long Chapter of the Association of Vietnamese Students and Overseas Compatriots. In a letter to his wife, Ton Nu Quynh Nhu, dated January 11, 1977, Huynh Phi Long, head of the chapter, wrote:

“During the fiercest years of resistance against My-Thieu, the heroic image, burning patriotism, and life of sacrifice of comrade Tran Quang Long reminded us daily to live better. In this new stage, we are profoundly grateful to you, your children, and your family – those who gave up a husband, a father, a son for the dream of our nation. The family of Tran Quang Long here in Germany grows larger and stronger every day. We think of him as we strive to study, to train, to prove worthy of the trust of the Party, of the people, and of the name of our chapter – contributing our best to the building of socialism in our homeland.”

Though his burning desire to see peace, to reunite with his family, and to behold his child’s face remained unfulfilled, his poems—ablaze with revolutionary spirit – and the letters he wrote to his wife became an enduring source of strength for his son, Tran Xuan Thang, helping him overcome life’s hardships and live up to the ideals of his beloved parents.

Tran Quang Long, who also wrote under the pen names Thao Nguyen, Chanh Su, Tran Hoang Phong, Tran Hong Trieu, and Cao Tran Vu, was born on February 6, 1941, in Hue, though his family hailed from the famous Bat Trang pottery village near Hanoi. He attended the prestigious Hue High School and studied Vietnamese literature at Hue University of Pedagogy. After graduating in 1965, he became a teacher at Cuong De High School in Quy Nhon, where he both taught and secretly wrote leaflets, slogans, and revolutionary poetry calling for peace.

In 1967, he moved to teach at Phan Thanh Gian High School in Can Tho. During this period, he often traveled to Saigon, where the General Association of Saigon Students invited him to serve as its cultural commissioner. He also became the founding chairman of the Student Creative Writing Association, preparing for the landmark poetry anthology Voices of Those Who Move Forward. He edited and contributed to many underground journals of the student resistance such as Sinh Vien Hue, Dat Moi, Dan, Sinh Vien Sai Gon, and collaborated with progressive literary magazines in Saigon like Tin Van, Dat Nuoc, Hanh Trinh.

After the Tet Offensive of 1968, he left Saigon for the liberated zones, joining the Alliance of National, Democratic, and Peace Forces of Vietnam. On October 11, 1968, he was killed alongside writer Tran Trieu Luat in a U.S. airstrike on the Central Office for South Vietnam’s cultural base in Tay Ninh.

Today, his name lives on – not only in poetry and memory, but also on the streets that bear his name in Ho Chi Minh City, Hue, and Da Nang.

Thu Hoan

Source: Great National Unity Newspaper