Such Was Our Twentieth Year

Amid the smoke and fire of the fiercest war, a young Hanoi student – an exceptionally gifted literary talent – took up his pen to write the fateful pages of his diary. In his words, he not only captured the innermost thoughts of an entire generation, but also, with uncanny foresight, envisioned the nation’s final victory. He was Nguyen Van Thac, the young soldier who forever remained at the age of twenty. Yet his writings have become immortal.

From Pen to Battlefield

Nguyen Van Thac was not an ordinary soldier. He was among the most outstanding young men of Hanoi at the time. Born in 1952 in Buoi village, into a large family of craftsmen, his childhood was marked by hardship and toil. His parents owned a small weaving workshop, but the American bombing campaign forced the family to sell their house and machinery and evacuate to their ancestral village in Co Nhue, Tu Liem. Their savings quickly ran out; his mother had to cut and sell grass to make ends meet, while young Thac both studied and worked to help support the family.

Yet adversity could not extinguish his innate brilliance. Throughout ten years of schooling, Thac was always an outstanding all-round student, with a special gift for literature. In Grade 7, he won second prize in Hanoi’s citywide literature contest. His crowning achievement came in Grade 10, during the 1969 – 1970 school year, when he won first prize in the nationwide Northern Vietnam literature competition. With such a record, he was selected to study in the Soviet Union. But the call of the Fatherland was more urgent. Following the national directive, most of the outstanding male students of that year remained to join the army.

While awaiting conscription, Thạc was admitted to the Faculty of Mathematics and Mechanics at Hanoi University, one of the most prestigious faculties. His intellect and passion for learning continued to shine. In his first year, he simultaneously studied the second-year program on his own, and was permitted by the university to advance directly to the third year. But as the war grew more intense, thousands of students had to set aside their studies and take up arms. On September 6, 1971, the brilliant young student Nguyen Van Thac was conscripted, donning the green uniform of a soldier.

He wrote in his diary on October 2, 1971: “Many times I still cannot believe that I am here. I cannot believe that on my cap rests a star, and on my collar are red insignia. The soldier’s life has come to me so naturally, so calmly, yet so suddenly.” The young man once familiar with white shirts and sky-blue clothes now embraced the green of the mountains and forests – the green of hope. It was the inevitable transformation of a generation who placed the fate of the nation above all personal dreams.

Thế hệ sinh viên Thủ đô “xếp bút nghiên lên đường chiến đấu”, chào quê hương, người thân vào chiến trường với tinh thần “thóc không thiếu một cân, quân không thiếu một người”, Hà Nội, năm 1971.

A Sensitive Soul Amidst a Harsh Reality

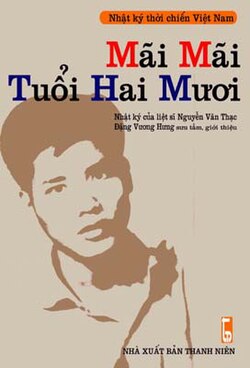

The diary, later titled Forever Twenty (Mai mai tuoi hai muoi) by poet Dang Vuong Hung and Thạc’s family, opened up a rich and profound inner world filled with reflection and yearning. In its pages, Nguyen Van Thac did not merely record events, but also captured his thoughts, his delicate perceptions of life, humanity, and the times he lived in.

**In the early days of military service, he was still the bewildered young man from Hanoi, far from home for the first time, living in the kindness of ordinary people. He wrote about the host family in Ha Bac (now Bac Giang) who gave up their three-room house to six young soldiers, and the kind 28-year-old woman who offered them bananas and peanuts for breakfast. He absorbed everything around him: “Walking on the fragrant straw, who could imagine a life more to be wished for? Even though such happiness is fragile, like the few who can truly recognize it as the happiness of life itself…” His literary soul permeated every line he wrote. Looking at bamboo leaves, he mused: “And yet, those bamboo leaves remain gentle, leading me into the serenity of the soul. How strange it is!” Passing through forests on the march, he marveled at the “mystical old woods” where “faces brush against the leaves.” He loved the eucalyptus trees and whispered to them to “tremble and lull me to sleep” when the time came for him to rest forever.

Thac was also a keen observer of people. Among the most striking entries were those about his fellow recruit, later poet Hoang Nhuan Cam. Thac quickly recognized his friend’s gift: “Cam (…) writes a lot; indeed, he has talent – or at least, a promising ability.” He described Cam’s verses as “pleasing, smooth, and polished” but lacking a certain “warmth that spreads.” He both admired and worried about his talented, free-spirited friend, hoping that the country would not let such a gift go to waste.

Yet Thạc’s inner world was not only poetic reverie. He often confronted himself with harsh honesty, at times painfully so. He wrestled with the great question of a young writer: “Can I do anything, can I contribute anything to the literature of resistance against America? Where to begin, and what path to follow?” He idolized the Soviet writer Boris Polevoy and the Vietnamese poet Pham Tien Duat, dreaming of writing great works about the war.

**Like so many young soldiers, he also could not escape moments of human weakness and fear. He wrote: “If I were to die now, it would be such a pity… Death is nothing – just a stray bullet or a blast. That tragic truth spares no one.” At times, despair overwhelmed him to the point of wanting to tear apart his diary: “My God! Never have I felt so disheartened, so hopeless as this morning… I dragged my feet along the trail – the trail as weary as the life I now drag along.”

But that was not cowardice. It was the ultimate honesty of a sensitive soul, a young intellectual confronting the brutal reality of war. What matters is that he overcame those moments of despair, continuing to march forward, to fight – until his very last breath.

A Summer Promise and the Prophecy of April 30

Amid the diary pages filled with reflections on the nation, on war, and on responsibility, there was always one gentle, tender figure who returned again and again. She was P., N.A., or Nhu Anh – the abbreviated names all pointing to the same young woman, his schoolmate Pham Thi Nhu Anh.

They first met in April 1971, at a gathering of Hanoi’s best literature students. Nhu Anh, the daughter of renowned lawyer Pham Thanh Vinh, was a year younger and one class behind Thac. Their innocent and romantic affection blossomed through quiet meetings at the Hanoi library. Though they met only five times, spending a total of some twenty hours together, those moments were enough to etch each other’s image indelibly in their hearts.

In Thac’s mind, Nhu Anh was inseparable from the sky-blue blouse she often wore. That image became a symbol, a haunting memory: “The blue sky is there for all to see, seemingly so close, yet impossible to reach!”

But the most miraculous, astonishing detail of their story lay in a promise tied to a historic date. In a letter to Như Anh on September 18, 1971, Nguyen Van Thac wrote a line that sounded prophetic: “On April 30, 1975, T. will answer P. the question: What is happiness?”

When he penned those words, it was nearly four years before the liberation of the South and the reunification of the country. No one can explain how a 19-year-old could foresee the exact date with such clarity. And it was no mere coincidence: in another letter dated September 4, 1971, he even “corrected himself” to his friend: “I remembered wrong, Lan (Thac’s alias) said it was April 30, 1975, when he would answer the question ‘what is happiness,’ not April 11, 1975.”

That promise was more than just a young man’s vow to the girl he loved. It embodied the unshakable faith and fierce optimism of an entire generation in the ultimate victory of the resistance. The “happiness” Thac promised to define was none other than the great happiness of a reunited nation, the day Vietnam became whole again. Though he did not live to fulfill his vow, his prophetic words came true – resounding forever with the land and its people.

“If I Do Not Return…”

Cuốn nhật ký ″Mãi mãi tuổi hai mươi″ của liệt sĩ Nguyễn Văn Thạc

In April 1972, Thac’s unit boarded a military train bound for the battlefield. That fateful journey was vividly recorded in his diary: “…arriving at the station, the soldiers burst out in excitement, the engine heading toward Hanoi – ‘We’re going!’ It meant we were certainly bound for the South. Hastily writing letters – As the train passed Cua Nam, white envelopes fluttered down to the streets below – ‘Please send these for us, please send them!’ – To tell our loved ones that we had left Hanoi…”

His diary, 240 pages long, was written over nearly seven months, amidst harsh training sessions and grueling marches with heavy loads. The final entries were dated late May 1972 in Ha Tinh. As if sensing his fate, he wrote a farewell to his beloved notebook:

“And now, farewell to the first diary of my soldier’s life. No time to read it again. No time to fix the hurried, clumsy words… Tomorrow, the day after… I must leave everything behind. I cannot let anyone read these thoughts. Unless I am no longer alive to keep them…”

And then, he asked himself the most haunting of questions – one meant for his own generation and those to come: “Yes, if I do not return, who will continue to write these pages in my place?” He wished that the unwritten pages would be “filled with joy and life,” not left “empty and mysterious like these.”

His farewell words became prophecy. In the fierce battle near the Quang Tri Citadel, signalman Nguyen Van Thac was gravely wounded, a shell fragment severing his left thigh. Though his comrades bandaged him, he lost too much blood. Growing weaker, he spoke his last words with calm and dignity: “The fact that I am still conscious means I am about to die… What I regret most is not being able to fight anymore… so many plans still unfinished.” He passed away in his comrades’ arms on July 30, 1972 – not yet twenty years old, with less than ten months in uniform.

Nguyen Van Thac never returned. He could not fill those blank pages with the joy and laughter he had hoped for. Yet his life, his soul, his ideals, and his uncanny foresight were carried on by the living. His diary, along with hundreds of letters, was carefully preserved by his elder brother Nguyen Van Thuc and his family, later collected and published by poet Dang Vuong Hung. Today, it remains an invaluable legacy for younger generations.

Private Nguyen Van Thac – the finest literature student of Northern Vietnam in his time, the young soldier who foresaw April 30 – now rests in the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Hanoi. He fell, but he still lives – forever alive in the pages steeped in love and ideals, forever alive at the age of twenty. He and his generation became immortal, a reminder that peace and reunification were won at the cost of the brightest lives, the unfinished dreams, and the purest souls.

Chu Van Khanh